You thought Dune Part Two was gonna come out and I wouldn’t write about the sandworms?? I bet you all feel very silly. I know that as recently as last week I wrote a post about bugs in movies/television, and here I am doing it again, but there is no way I wasn’t going to address the worms, and there’s no better time for that than now.

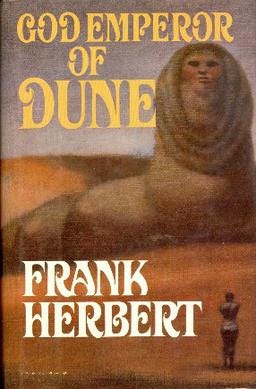

Sandworms, the giant slithery natives of Arrakis, the desert planet created by Frank Herbert and the sole reason that the Star Wars movies are so preoccupied with Tatooine. We love them! They’re big, they’re iconic, and they, like most other things Herbert sprinkled into his vast space opera, have a complex and fascinating connection to everything that goes on in the Dune books. I’m not going to go into an exhaustive biology of a fictional animal here, since there are plenty of wikis online if you’d rather read all of that, but I do want to talk about one thing that both the books and the new movies address only subtly, and that will require a little bit of context. Like a worm into desert sands, we’re diving in.

The sandworms are the largest native animal living on the surface of Arrakis, a.k.a. Dune, a planet known for two things: being almost completely inhospitable, and being the only home of the valuable hallucinogenic drug spice. Arrakis is the most important planet in the universe because spice occurs nowhere else, and it’s essential for space travel (long story short, there are no computers in Dune, so all the computing to jump spaceships from place to place is done by mutated humans who subsist on a constant, heavy dose of spice for their entire lives).

No one except the Fremen, the native people of Arrakis, know where spice comes from—it basically pops up in “beds” on the surface of the sand, and is found by scouts and mined by machines that sift through the deposits. The Fremen know (and this is a spoiler, so if you don’t want to know yet, there’s your warning) that spice comes from the sandworms, a waste byproduct that comes from the worms’ bodies as they drift through the sand, leading the Fremen to nickname them “makers.”

The sandworms are responsible for spice, and they’re also responsible for Arrakis’ ecology. Arrakis is a desert planet because of the sandworms, which it turns out were nonnative species introduced millennia earlier, and in their moisture-sucking larval forms (sandtrout) were able to systematically remove all traces of water from the surface of the planet. Arrakis was once a lush paradise not unlike Earth, but water is poison to the sandworms, so they terraformed it away.

Because the worms are so massive and so important to the ecology of their world and to the creation of the thing that makes Arrakis so special, they’ve taken on a special sacred significance to the Fremen, who call them Shai-Hulud, “Old Man of the Desert,” and see them as a physical manifestation of their god. But there is another part of the Fremen religion that exists at odds with the sandworms. Because Arrakis is so precious to the empire, it’s in its wealthy noble houses’ best interest to keep the planet as dry and uninhabited as possible. The Fremen, on the other hand, dream of a thriving homeworld full of water, and believe that, eventually, their messianic Kwisatz Haderach will lead them there. The only problem is, if you allow oceans and forests and rain to take over Arrakis, you lose the desert, and you lose the sandworms, and you lose the spice.

It’s a conundrum that will preoccupy the latter books in the Dune series—the ethical impasse between giving the Fremen the world they’ve always wanted, and thereby doing away with not only their way of life, but also the way of the rest of the human universe. Space travel, trade, government, and even communication between planets would be impossible if Arrakis didn’t remain a desert. Herbert steeped his books in a lot of the contemporary concerns of his day (many of which remain the concerns of our day), and one of those was environmentalism, the different forms it takes, the different questions it engenders. It was environmental tampering that allowed the sandworms to proliferate, and it is environmental tampering of a greater magnitude that will be their undoing. With the sandworms, Dune demands its characters and its readers to decide what’s more important.

Thanks for a nice framing of the morality of ecology.