It seems like every year at around this time we start seeing headlines about how THIS cicada swarm will be the cicada swarm to end ALL cicada swarms. Despite the fact that this is probably just an SEO trend that multiple outlets figured out generates a lot of guaranteed clicks, it has kind of been true for the past few years. Remember when Brood X, one of the largest broods of periodical cicadas in the world, hit Washington, D.C. in 2021, and the seat of the nation’s governing power was held hostage by a swarm of screaming, red eyed beasts?

This past month, you’ve probably seen those dreaded headlines pop up again, promising another summer-long cicada plague. This time it’s hitting Illinois, and, yes, it’s going to be big. We’re not just getting one brood this year, we’re getting two.

How is that possible, you may be wondering. If all of these broods are on a strict rotating schedule, how can two hatch out of the ground at once? To explain this, I need to explain what these cicadas actually are. First of all, if you’re an American and you’ve seen a cicada in your life, it’s likely been an annual cicada, likely of the genus Neotibicen—large, hefty insects with transparent wings and white bellies, with a camo-like pattern of olive greens, browns, and blacks covering their heads and abdomens. These cicadas are referred to as “annual” because they emerge every year no matter where you live in eastern North America.

The brood cicadas are called periodical cicadas, not because they read lots of magazines (ha ha) but because they do not emerge every year. In the eastern United States, there are seven species that make up the genus Magicicada, and they’re separated into two types: those that emerge every seventeen years, and those that emerge every thirteen years. Magicicada cicadas are black with piercing red compound eyes and bright orange veins in their wings, a completely different slightly more evil vibe from the green guys we get every year. The nymphs live underground for thirteen or seventeen years, maturing through five instars. Once they reach the near adult stage, they wait under the ground for the surface temperature to warm up enough to emerge.

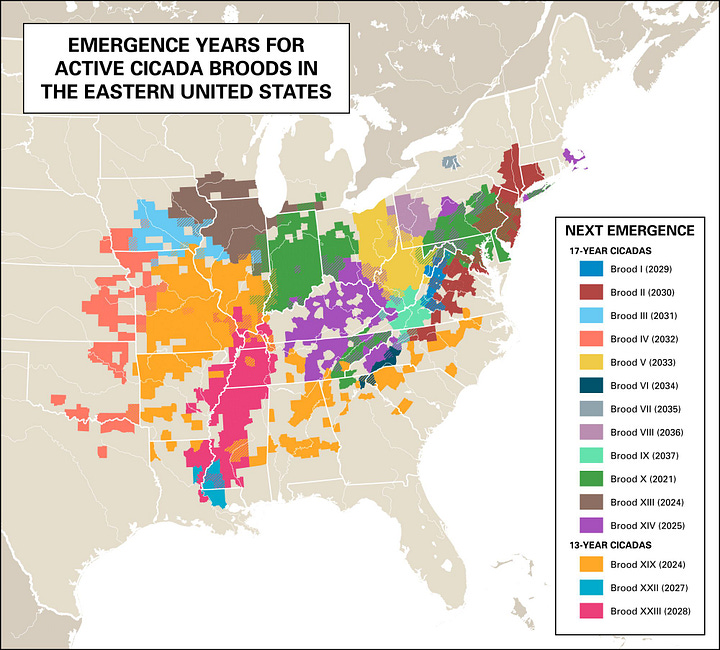

This summer, the emergence of the seventeen-year Brood XIII and the thirteen-year Brood XIX will happen at the same time, with Brood XIII popping up in eastern Iowa and southern Wisconsin, and Brood XIX covering western North Carolina and South Carolina, northern Georgia, and parts of Alabama and Arkansas. Both broods will pretty much cover the entire state of Illinois, but interestingly won’t likely overlap, as each brood tends to stick to its own territory. Brood XIX is often called the Great Southern Brood, as it’s the biggest brood of thirteen-year cicadas in the country.

This occurrence is special for a number of reasons. We haven’t seen a seventeen-and a thirteen-year brood emerge at the same time since 2015, and haven’t seen this particular combination since 1803. It’s also the first time since 1998 that two broods will emerge in such close proximity to each other. Citizens of Illinois will be lucky enough to see all seven species of periodical cicadas at once—Springfield in particular is one of the few places where both types could be present simultaneously—but we’re not likely to see tons and tons of cicadas in one place. Instead, they’ll be more evenly distributed across many places.

Brood emergence is classified as a type of “biomass pulse,” an extreme increase in the number of individual living things in an area that often comes with its own environmental complications. The periodical cicadas’ brood strategy is an antipredator adaptation: the more cicadas there are in an area, the more chance some of them will survive being eaten long enough to mate and reproduce. The cicadas have been doing it for millions of years, surviving the glacial pulses that shaped the modern landscape of eastern North America.

D.C. is still seeing the effects of the 2021 emergence. This great piece in DCist explains how a biomass pulse like a cicada emergence temporarily “rewires” an entire food web. The local predators (birds) target more cicadas and fewer of the other bugs in the area, allowing the other bugs to reproduce more than they normally would, creating an influx that in turn impacts the health of the plants that caterpillars, for example, use for food. In 2023, oak trees in the region had a mast year—a season where they produce an unusually high amount of acorns. It’s no coincidence that this tends to occur two to three years following a cicada emergence.

So, what can we expect from this year’s broods? It’s difficult to predict exactly how many will come, but it will definitely be more widespread than usual. A periodical cicada emergence is always something special; nothing like this happens anywhere else in the world. Here, every year, the cicadas remind us to spend time outside, to gather together with friends, to scream.