ISSUE #23: Interspecies Communication Is Sweet

Something something “the birds and the bees” something something.

Humans and animals have been living alongside each other for tens of thousands of years. We turned wolves into dogs something like 30,000 years ago, and started keeping hooved herd animals like sheep and cattle about 10,000 years after that. In all of these interactions between man and beast, the beasts play a subservient role: we take from them what they provide, and in exchange their basic needs—food, shelter—are met. We alter their genetic identities with domestication and breeding, making them meatier, slower, faster, cuter.

There have been stories of humans and wild animals working together for a common gain, usually food. Some say wolf domestication occurred because wolves, being pack hunters, became accustomed to following human hunters around when they were hungry. Dolphins have been seen following boats and herding fish into nets, using the human fishermen as obstacles to make their hunting easier. Aboriginal whalers in Australia would follow the signals of orcas to find whales, allowing the orcas to eat the whales’ tongues after they had killed them. There is only one animal, however, that has been proven to specifically communicate with humans to find food, a cultural practice some believe has been going on for more than a million years. It’s still unofficially Bee Month, but this issue of Bugstack is also about a bird.

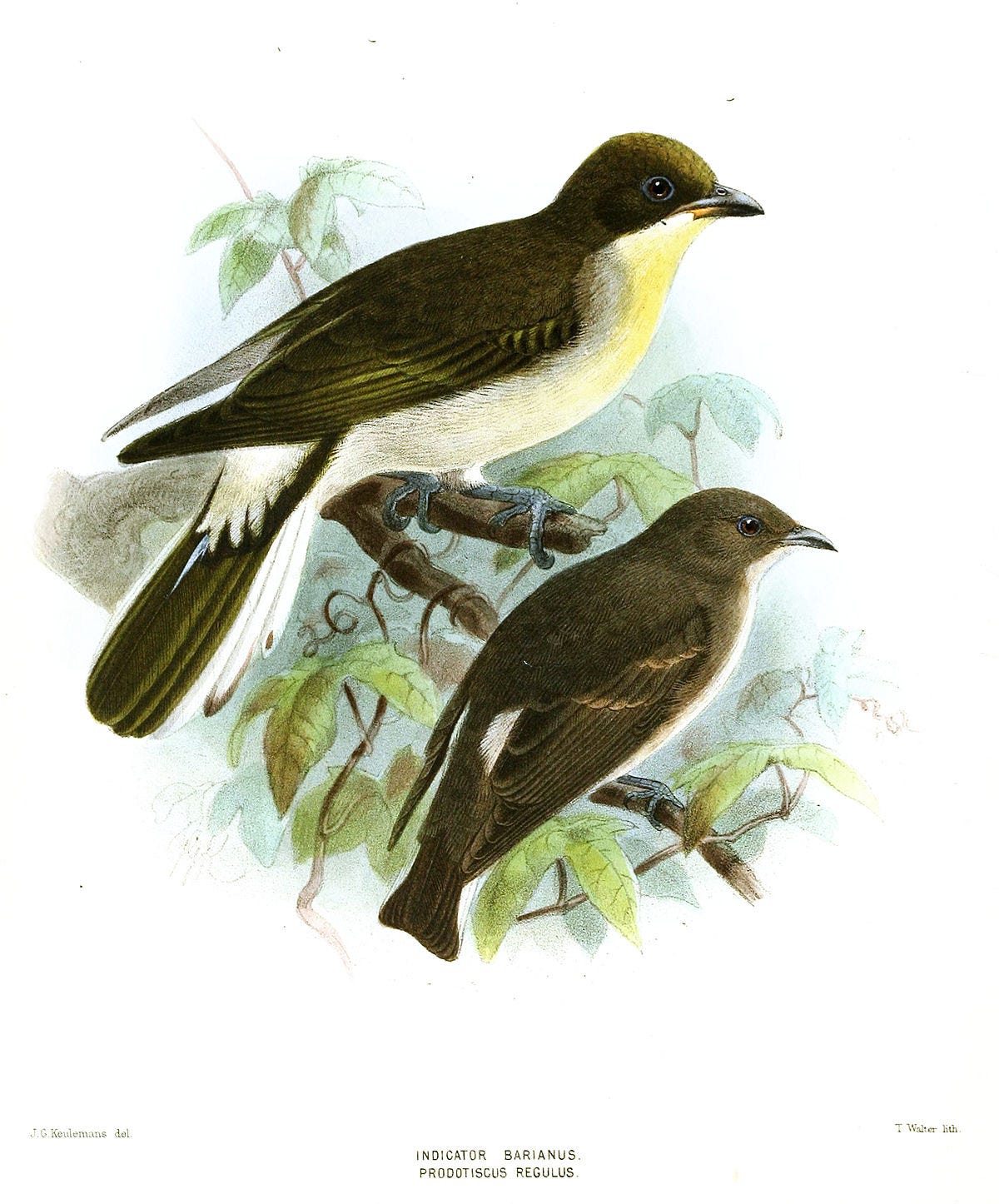

In the woodlands and savannahs of sub-Saharan Africa lives the greater honeyguide, Indicator indicator, a small brown bird with a unique way of getting food. The word “unique” isn’t strong enough to indicate how special this behavior is: the honeyguide is the only living thing in the world that does what it does.

Honeyguides eat bees. They eat the bees themselves, their larvae, their honey, and even the wax of their honeycomb (honeyguides are one of a few bird species that can actually digest wax). Beehives aren’t that hard to find, but for the small honeyguide, they’re almost impossible to get into without getting stung.

The greater honeyguide has a way to get around this problem: just use humans, who, with their smoke and their tools and their dexterous hands, have a much easier time of getting into a bee nest than a small bird would. Some beehives might be wedged in deep crevices the bird can’t access, or guarded by enough bees that their combined stings might be deadly. So the honeyguide finds the nearest group of people and starts making a series of aggressive chirp-whistles—the signal that various tribal people in Africa have learned means the bird is hungry, and it knows where the honey is.

A honeyguide will, quite literally and quite intentionally, guide a person to a beehive, knowing that, when the person is done harvesting what they need, there will likely be something left for the bird. It’s a practice called foraging synchrony, or mutualism: everyone (except the bees) benefits. In fact, the folklore of many African nations stresses the importance of paying back the honeyguides with extra comb, or next time the bird might lead its follower into the jaws of a lion or a venomous snake. (The Hadza people, however, have a different practice: they burn or bury the extra honeycomb in order to keep the honeyguides hungry, and more eager to guide them to more hives.)

Honeyguides in different regions have even learned to recognize humans’ calls—a form of cultural coevolution. The Borana of East Africa use a loud whistle, called a fuulido, to summon the birds. The Yao of northern Mozambique have an unmistakable “BRRrr-hmm” call to start a honey hunt that adult birds have learned to respond to. In Zambia, they’re attracted by the sound of chopping wood.

There is a dark half to the honeyguide, a shadow self that throws their partnership with humans into a new light. Honeyguides are brood parasites, meaning that the adult female birds lay their eggs inside the nests of other birds. When the honeyguide chicks hatch, their beaks are equipped with a barb that they use to violently kill their would-be adoptive siblings. Instinct blinds the parent birds to this betrayal, and they feed the honeyguide chick as if it was their only offspring. It’s a bit of an odd start for a bird with such a complex behavior, leading many to believe that the drive to guide has evolved into an instinct, innate and imprinted from birth.

The greater honeyguide’s guiding behavior is also under threat in some parts of Africa. In urban parts of Kenya, where refined sugar has become easier to access, the honeyguides have gradually stopped attempting to catch humans’ attention. A cultural practice found nowhere else on Earth (that has likely been around since before Homo sapiens) is in danger of dying out with the advent of homogenized food. It’s easier to buy your honey at the store instead of trudging through the brush after a bird. But does it taste as sweet?

Beautiful video!