ISSUE #07: Did You Know That Cockroaches and Praying Mantises Are (Maybe) Related?

I learned something new at the bug museum!

Hello again and welcome back to Bugstack, which was forced to go on an unplanned hiatus last week due to its sole contributor (me) contracting the novel coronavirus. I’m fine now, though two weeks of canceling social plans and slogging through the “COVID fog” to get actual work done was less than fun. Luckily, the bugs are still here, and this post is all about something I learned right before the fever and chills hit, when I FINALLY visited the brand new Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation, attached to the backside of NYC’s American Museum of Natural History like, well, some giant insect nest.

I’ll probably do a post about the visit itself next week, because I didn’t want to deal with transferring all my photos to my computer and then to Substack, which isn’t actually difficult except for the fact that my computer and my phone refuse to notice each other these days so I’m forced to send a string of emails to myself if I want to add my own photos to anything. It’s just annoying, and I refuse to let this Substack be a source of annoyance. Yes, I’m still writing and scheduling the posts on Thursday nights, but I’ve made my peace with that.

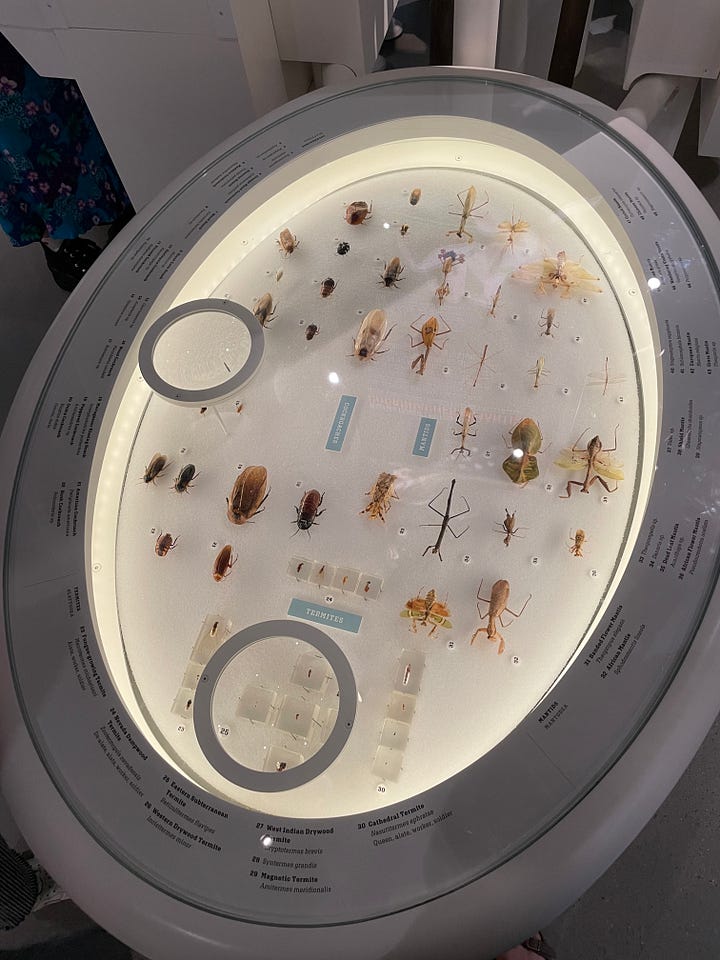

While checking out the “Insectarium” portion of the museum—which also contains a 360-degree theater, a butterfly vivarium, and a library—I was immediately drawn to the specimen boxes that marked every insect order on display. There were live specimens in tanks, which I also loved, but there is something visually appealing about a bunch of preserved insects lined up in a frame, their limbs and wings arranged so you can plainly see their symmetry and their variations.

The bugs were arranged by order, which, if you remember your Intro Bio, is the fourth category down the levels of classification in modern taxonomy—that is, the very lengthy name that distinguishes one living thing from another. Insects make up the class “Insecta,” in the phylum “Arthropoda,” in the kingdom “Animalia,” and so on. An order is the next level down from class, indicating the broad group an individual belongs to. It’s a little bit more specific than class, but more inclusive than the next level down (family), meaning that many orders are disputed, or only recognized by a few scientists, or already out of date. Basically, if your argument is strong enough, you can convince scientists of anything. It’s important to remember that all of this stuff is made up and subject to change.

But it’s not nonsense, which is what I discovered when I started paying attention to how the specimens in the Insectarium are organized. One display in particular stood out, in which praying mantises were pinned alongside cockroaches and, down at the bottom, teeny tiny termites. At first I thought it was an aesthetic choice, until I looked at the description, which noted that all of these bugs are currently considered part of the superorder Dictyoptera. “Superorders” are essentially big groups that contain multiple orders, which are then sometimes called “suborders.” Dictyoptera, the current thinking goes, contains both Mantodea (the order of mantises) and Blattodea (the order that includes both cockroaches and termites (which are also related!! who knew!! not me!!)). The word “Dictyoptera” comes from Greek—dictyon meaning “net” and pteron meaning “wing”—the “netwinged” insects, so called because you can clearly see the network of veins running though their wings.

There are other similarities indicating that all of these bugs may have at one time shared a common ancestor: they have two pairs of wings, and the top pair is more leathery and folded longways close to the body; they have long, thin, wispy and highly sensitive antennae; the females lay batches of eggs in capsules called oothecae that they either carry around with them or attach to plants; their feet have five segments; their middle and hind legs are spiny; their mouths are built for chewing. (Termites don’t really fit with most of these descriptions—they are instead considered a branch related to but far removed from cockroaches, if they are considered related at all.) Sometime during the Cretaceous period, a group of former cockroaches weaponized their forelimbs and stood upright while the rest kept crawling through the leaf litter, and after millions of years they barely look anything alike.

I know this post is long and has a lot of “science stuff,” but I found it really interesting that two groups of insects that could not be more opposite from each other in our minds could actually be semi-close cousins, taxonomically speaking. Who knew that mantids with their elegant bodies and voracious predatory insects, and cockroaches with their gross scavenging habits and proclivity towards our well-kept pantries could share any similarities, let alone be similar enough to be displayed together in a museum. Mantids and roaches are two sides of a coin, two completely opposite evolutionary paths that emerged from a single point, allowing nature to have it both ways for a hundred million years.

I love the deep scientific stuff! I'm also the only person I've ever met who doesn't mind cockroaches, granted I've never been horribly infested with them. They're extremely prevalent around the outside areas of my work and I just consider them my little friends. They're so harmless that I don't entirely get people's ire or hatred for them.

Unbelievable! Still absolutely despise cockroaches! Not even an ancestral link to my favorite insect can change that.